On 9th December, 1854, Lord Wilton, Commodore of the Royal Yacht Squadron, wrote to his fellow members urging them not to be forgetful of others and to support the alleviation of the privations of ‘our gallant countrymen in the Crimea’. He suggested this objective could not be better accomplished than by fitting out a large yacht and ‘filling her with those comforts and luxuries which we have reason to believe would be most appreciated by them’. Lord Wilton thought this measure would be extremely popular amongst the members of Squadron as so many were connected with the Army.

Arrangements were made with Messrs. Drummond of Charing Cross for subscriptions to be received and later the Royal Yacht Squadron schooner Fairy, owned by J.H. Elwes, was sent to Balaclava where she unloaded the good things required to alleviate the suffering of the men in the trenches in front of Sebastopol. The schooner Fairy was accompanied by the Esmeralda, Claymore and a number of others.

The Earl of Cardigan gained permission from Lord Harding, then Commander-in-Chief, to travel independently of his brigade to the seat of war. He was accompanied by an ADC and left London for Paris on the 8th May, 1854. He gave a dinner party at the Café de Paris on the 10th and was entertained by Napoleon III and the Empress Eugenie at the Tuileries, leaving Marseilles by French steamer on the 16th. On the 21st May, the Earl arrived at the Piraeus, spending a few days sightseeing in Athens. On the 24th May the ship anchored off Scutari, the British base where he met his old sparring partner, Lord Lucan, his immediate commander and brother-in-law. Lord Cardigan had no intention of being ordered about by Lord Lucan and went over his head, applying to Lord Raglan for the necessary permissions.

On the voyage out, Lord Cardigan had not been well. He suffered from chronic bronchitis and did not appear to have the physical capability for the job. Indeed, Lord George Paget said on the 13th October, ‘I believe clearly he is ill, and that this will be the end of him’. On the evening of the 13th October, Cardigan was not with the invalids on the ships but sitting in his tent on a bullock trunk, eating soup from a jug, boiled salt pork, and drinking Bulgarian brandy mixed with rum ‘to make it more appetising.’ Help was at hand, for Hubert De Burgh, Cardigan’s brother-in-law, arrived aboard Cardigan’s yacht RYS Dryad in the harbour at Balaclava. Captain Nolan, killed at the Charge of the Light Brigade, nicknamed Cardigan the ‘noble yachtsman’ and the name stuck.

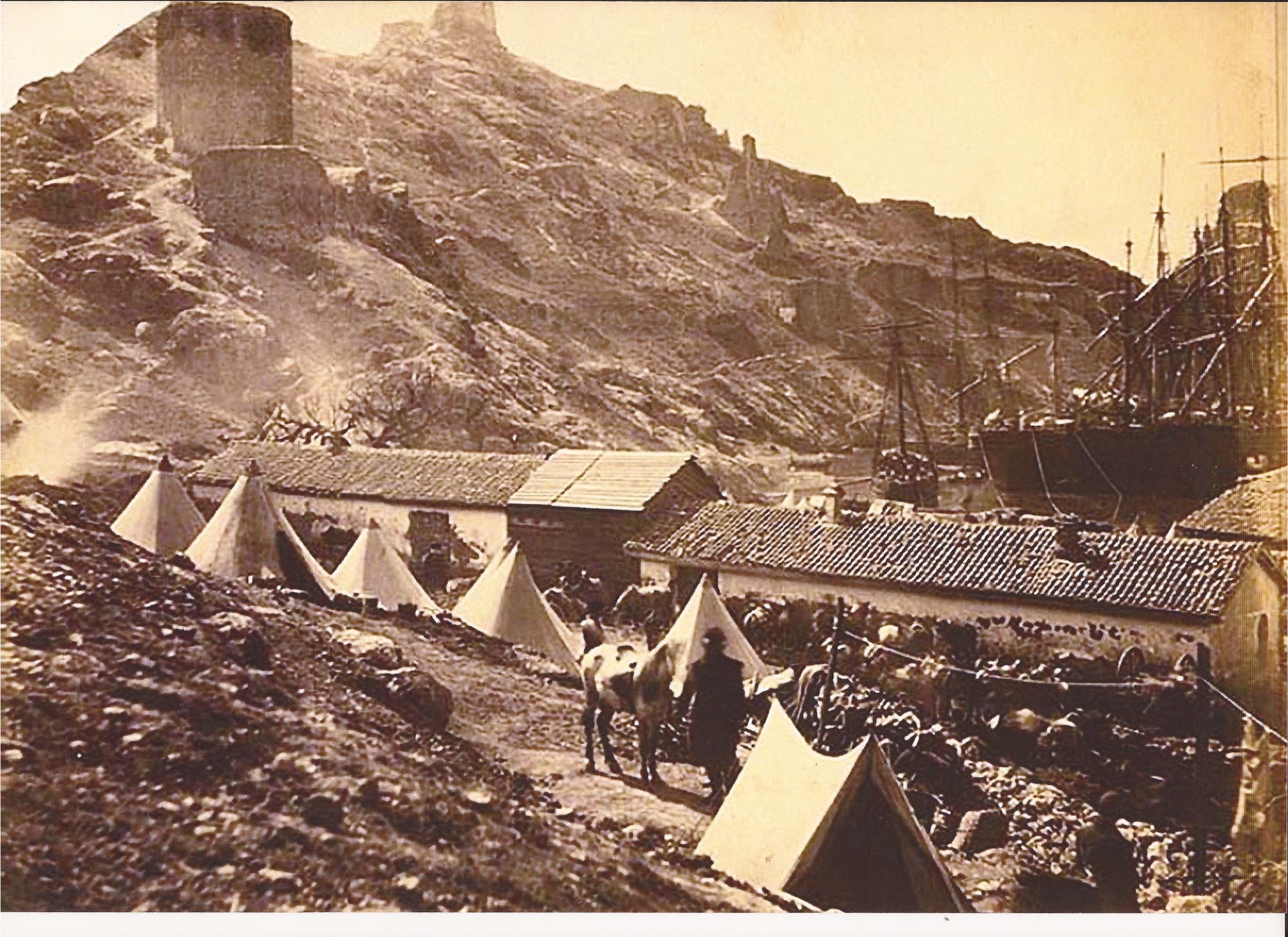

There is a model of RYS Dryad in store at the Science Museum (Fig. 1). This gives a clue to the cutter pictured in the Illustrated London News anchored off Balaclava (Fig. 2). In turn, this led to the identification of Dryad alongside the harbour wall connected by a gang plank, in the photographs of Roger Fenton (1819-1869) (Fig. 3). There is no sign of Cardigan’s horse, Ronald, that carried him throughout the campaign, including the Charge of the Light Brigade. The horse was eventually pensioned off at Deene, Northamptonshire. Ronald’s head has pride of place in the house as a celebrated member of the family. No doubt during his time at Balaclava he was looked after by a groom and brought to the shore end of the gang plank so that Lord Cardigan could rejoin his brigade each morning, arriving on the Heights at 10.30 a.m. after a ride of six miles.

Cardigan was considered one of the invalids at Balaclava and received permission to sleep aboard Dryad for medical reasons. Later, an Army Medical Board was convened on board Dryad to consider the case of Lord Cardigan. The original idea that he should be sent to Malta or Naples for a period of recovery was not thought the right solution and it was decided by the Board he should return to England.

Cardigan told Captain Duberly, Pay Master of the 8th Hussars and husband of the remarkable Fanny, ‘My health is broken down; I have no brigade. If I had a brigade, I am not allowed to command it. My heart and health are broken. I must go home.’ Fanny Duberly records she was sincerely sorry for him.

Lord Stratford de Redcliffe invited all senior officers to a ball at the British Embassy in Constantinople. He was Ambassador and the invitation included brothers-in-law Cardigan and Lucan. After the entertainment, Cardigan sailed from Constantinople aboard the Ripon for Marseilles. Again, he was received by Napoleon III and invited to dine at the Tuileries in Paris but he could not squeeze into his dress shoes so stayed at the Hotel Westminster instead. The hero of the Charge of the Light Brigade landed at Folkestone on the 13th January, 1855. He was recognized by the crowd and the cheers resounded though they were interrupted by the crashing cords of brass and cymbals playing the most characteristic of all English triumphal music, Handel’s ‘See, the Conquering Hero Comes’ from the opera Judas Maccabaeus. The same triumphal music was played at every railway station Cardigan passed on his way to Deene. A portrait of him called ‘The Cardigan Galop’ pictures him cutting down the Russian gunners with one hand while he led the brigade in their famous attack.

RYS Dryad, a cutter of 85 tons, originally owned by William Delafield, was bought by Lord Cardigan in 1854. He sold her in 1859. She disappeared from the history books after Lord Cardigan’s ownership and is not recorded in Hunt’s Universal Yacht List or the first edition of Lloyd’s Yacht Register of May 1878.

There is some doubt as to whether Cardigan rode straight back to his yacht from the Charge of the Light Brigade or whether he paused to enquire after some of his wounded men, as some record. Whatever happened, the ‘noble yachtsman’ was a public hero.

***