The contribution to the Falkland Islands campaign by Lieutenant Colonel Ewen Southby-Tailyour, described in the two passages below, is a fascinating illustration of the effect that a single yachtsman can have on the outcome of a war. Stationed in the Islands from 1978 to 1979, Southby-Tailyour used his free time to make a survey of the coastline, which he regarded as an unexplored paradise for yachtsmen. When Argentina invaded the Falklands in April 1982, he offered his drawings, paintings, notes and photographs to Brigadier Julian Thompson of the Royal Marines, who later wrote: ‘after a few minutes it was clear that he and his notebook and charts must come south with us… He became a key member of the team planning the amphibious assault.’ After the war, Southby-Tailyour continued his explorations and pioneering surveys in high latitudes. He was UK Yachtsman of the Year in 1982, and winner of the Camrose Award of the Royal Yacht Squadron in 2001. A distinguished diplomat and author, he has written a series of books on military and naval subjects, including Blondie: A Life of Lieutenant-Colonel HG Hasler DSO OBE [Leo Cooper, 1998] and Exocet Falklands. The Untold Story of Special Forces Operations [Pen and Sword, 2014]. He was editor of Nothing Impossible, A Portrait of the Royal Marines [Third Millennium, 2012]. The first of his books was Falkland Islands Shores, published in 1983.

We reproduce here, with the authors’ kind permission, Julian Thompson’s Foreword and Ewen Southby-Tailyour’s Preface to Falkland Islands Shores.

Foreword by Major General J.H.A. Thompson CB OBE (Commander of 3rd Commando Brigade, Royal Marines, during the Falkland Islands Campaign, 1982)

I first met Ewen Southby-Tailyour when he joined 45 Commando Royal Marines as a Second Lieutenant in Aden in the early 1960s. I was the Senior Subaltern, or Lieutenant, in the Commando and responsible for the discipline and general behaviour of the other Subalterns. I quickly recognized that Ewen with his sense of fun and high spirits would get into all manner of scrapes; he did, but in the nicest possible way.

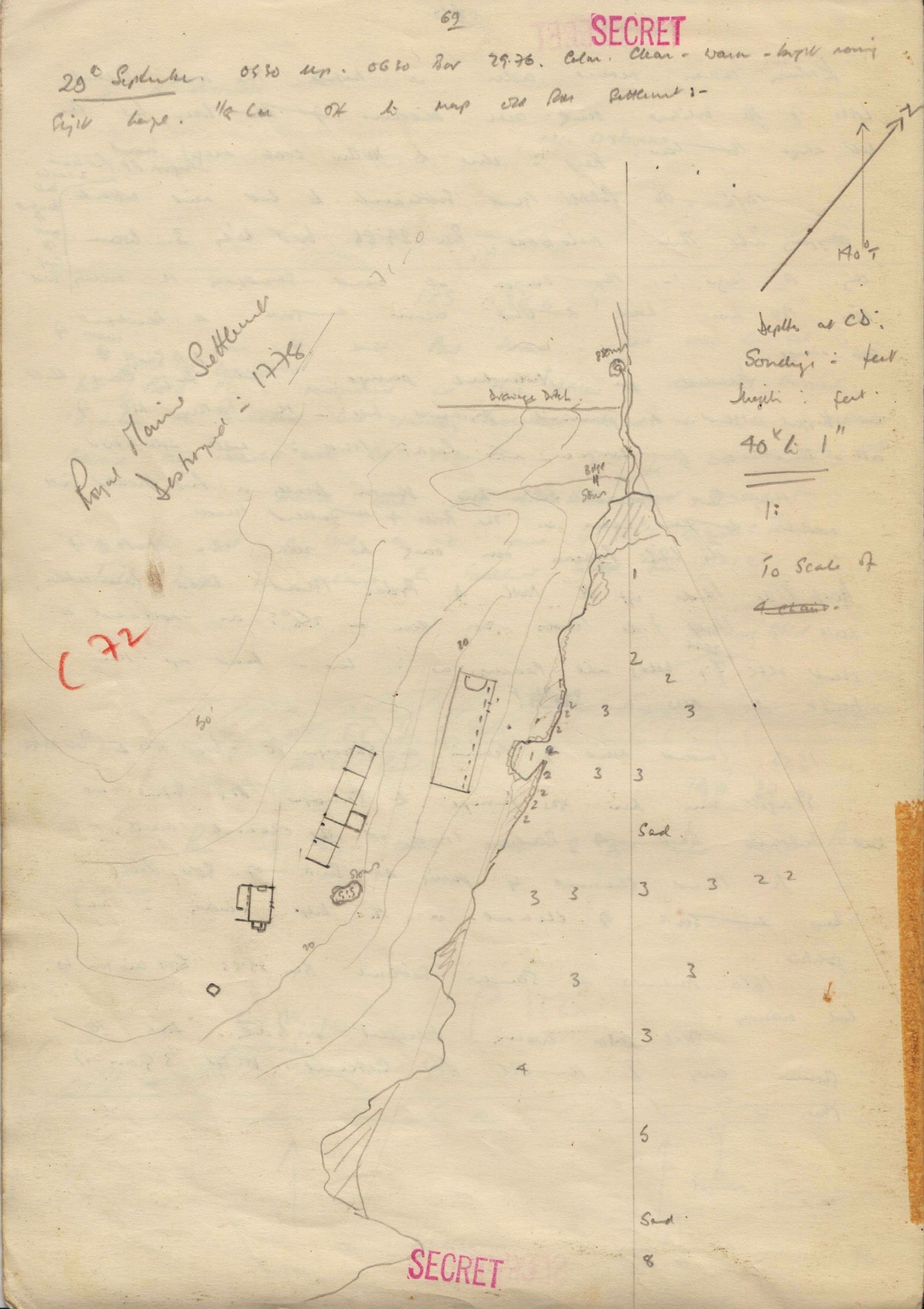

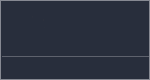

Twenty years later, after soldiering in a great many places round the world, including being decorated for gallantry by the Sultan of Oman, and sailing thousands of miles, Ewen made a unique contribution to the successful outcome of the campaign to repossess the Falkland Islands in 1982. Unique is an overworked word these days, but is chosen with care and fits the case precisely. This book is the result of Ewen’s work as the Officer Commanding the Royal Marines Falkland Islands Detachment in 1978 and 1979, when he spent a great deal of his time sailing around the coast of the Falkland Islands producing in pencil in a rather dog-eared notebook what you now see in print in this book. It is not an exaggeration to say that Ewen fell in love with the Islands and their deeply indented coastlines. When he returned from his one-year tour he tried to find a publisher for his notes, but at the time there was little interest.

On 2 April 1982, when Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands, Ewen presented himself at Hamoaze House in Plymouth, where I had set up my Headquarters, bringing with him the pilotage notebook and a large roll of charts. After a few minutes it was clear that he and his notebook and charts must come south with us — not that he needed any persuading. He became a key member of the team planning the amphibious assault.

The 64,000 dollar question that any Commander planning an amphibious operation asks is ‘Where shall I land?’ To help him decide he will want to know a great deal about a number of beaches that, after examination of the charts, look as if they might be the place he is searching for. Having refined the possibilities down to a short list, he will want to send men to look at these beaches as covertly as possible to gather as much detail as they can. The problems facing a Commander choosing landing beaches on the Falkland Islands were that, in 1982, the charts were not, in many areas, up to date; the soundings did not, in most places, go close enough inshore; the kelp which is such a hazard to the propellers of small boats and landing craft was not plotted accurately; and so, from the information contained in the current charts, it was not possible to produce a short list of beaches to which the Special Boat Squadron (SBS) could be sent to glean the detailed information. There simply was not time to send SBS teams to more than half a dozen beaches. Curiously, the Falklanders themselves have a very sketchy knowledge of their own coastline, so no help would be forthcoming from Falklanders who happened to be on leave or living out of the Islands in April 1982.

However, Ewen and his notes solved the problem. His knowledge and his notes, both unique, enabled the planners to select only those beaches which were suitable for a landing for SBS reconnaissance and thus save precious time. The most vivid picture I have of Ewen during the passage south is of him in his ‘home’, which he had set up in the bath in the Senior Officers’ bathroom in HMS Fearless, poring over his charts, producing answers to the myriad questions the planners had posed.

Not only was he the greatest living expert on the sea approaches to the Islands, he also had extensive knowledge of the flora and fauna and possessed a large collection of coloured slides. Travelling from ship to ship, as we steamed south or paused at Ascension, he lectured to every marine and soldier in my Brlgade on the terrain, animals, birds, fish, plants and almost every conceivable aspect of the Islands we were approaching. He produced, on his own initiative, comprehensive survival notes which were run off and issued to every marine, soldier and aircrew.

Ewen led the waves of landing craft into San Carlos Water on D-Day, to beaches selected because of the information contained in his pilotage notes. Indeed, one beach could not be checked out by the SBS before D-Day because of a combination of events which prevented a detailed reconnaissance. Ewen, aided by his own notes, was able to guarantee that we could land troops on it and we did. After the initial landings, Ewen, using his pilotage notes, led a number of subsequent landing craft sorties to several destinations.

I hope I have made it clear why I described his contribution to the success of the campaign as unique. Any campaign is the sum of the efforts of all those who participate in it, but if I was asked to name one man whose knowledge and expertise was irreplaceable in the planning and conduct of the amphibious operations, I would, without hesitation, name Ewen Southby-Tailyour. It is therefore with pride and humility that I write this Foreword to his book.

Preface by Ewen Southby-Tailyour

That this book has been published at all is a tragedy. Under happier circumstances my original notes on the coastlines of the two hundred or so islands that make up the Falklands archipelago would have received no publicity; they would have remained in their original pencilled form available for inspection and copying by members of those yacht clubs of which I am a member.

I cannot ignore the fact that had there been no Argentinian invasion of the Falkland Islands on 2 April 1982 there would have been no demand for the information that I have compiled. I would rather my notes had remained in obscurity. But the invasion is part of Falkland Island history and the Islanders may now look forward to a future of freedom, which must include the freedom to cruise these most beautiful unspoilt waters in peace.

In 1977 I joined the Royal Marines based at Poole in Dorset to form a detachment of Marines for Falkland Island service. In March 1978 we landed on the public jetty from HMS Endurance to begin a year’s tour. As it was an unaccompanied tour it was not as popular as it should have been, and even the younger unmarried Marines found that the local social life did not replace what they had left behind. I was fortunate as I (and two other Marines) had made private arrangements to fly out my family by courtesy of the Argentinian Air Force. That being so, the children had a right to be disappointed, for from our first week in the Islands it became clear that there was work to be done in studying the waters for cruising yachtsmen. Thus I saw little of my family during that year, although having them in Stanley rather than in our house on Dartmoor helped me to concentrate on my self-imposed task.

Before leaving for the Islands I had carried out some research on the waters of the Falklands and discovered that they were indeed largely uncharted from the yachtsman’s point of view and that this was a gap that needed filling, even though, as was so in our case, only three yachtsmen a year might visit Stanley. The original concept had therefore been to write a private set of sailing instructions for the Royal Cruising Club and Royal Naval Sailing Association on whose committees I then sat.

The plan then had been to have my 5-ton sloop Black Velvet shipped out to the Islands on the Falkland Islands Company’s charter vessel, but the price for a one-way trip as deck cargo was over £2,000 which, when added to the cost of flying out the family, meant that something had to give. Black Velvet lost! The Royal Marines had given me permission to sail back at the end of the year so it was a glorious opportunity lost. It became clear very quickly, however, that had I had the yacht in the Islands I would have covered only a few hundred miles in the year which would not have been very satisfactory as there are some 15,000 miles of coastline to be explored.

Part of the duties of the Royal Marines Detachment was to patrol the outer islands, to give military training to the Settlement Volunteers and to ensure that no illegal landings took place, as had been the case on Southern Thule in the South Sandwich group of islands a couple of years before. To carry out these three tasks we possessed a 150 ton Motor Fishing Vessel called the MV Forrest. She was named after a particularly effective Roman Cathiolic priest who had served the community earler. Forrest was skippered by Captain Jack Sollis, MBE, BEM, who was, and even in his retirement still is, the most knowledgeable seaman in the Islands. He understood the Islands so completely that I never once saw him consult a chart and yet he knew every rock, danger, tide and eddy that existed. It was not unknown for him to advise on, and correct, some of the more modern surveys. However, he viewed the waters through the eyes of a merchant seaman; the fascination for me was to interpret his knowledge for the use of yachtsmen. In many instances he would navigate Forrest to an area from which I would then carry out my more specialist type of study. Without Jack Sollis and his long-suffering crew I would have wasted much valuable time studying places that were of no value to a yachtsman. In effect therefore this is Jack Sollis’s book.

With the sailing instructions contained in this book the yacht’s navigator will find help to many of the anchorages and passages throughout the Islands. Unless I particularly state to the contrary, I myself have visited every place. To record so much information and be satisfied that it was correct and accurate enough for a shallow draft yacht I felt that as often as possible I should put into practice the information that I had recorded. To this end and, as it were, to test the system, I would often navigate the Forrest from my own sailing instructions but, more important, I would also navigate any yacht that called in to Stanley. In this respect I have to thank the three joint skippers of the Norwegian ketch, the Capricornus.

Sailing the Falkland waters is not a dangerous adventure but it has seldom been attempted by outsiders since the days of commercial sail. The reason is simple to understand. Many of the yachts that put into Stanley have just rounded Cape Horn or are just about to do so. Either way it is a dramatic event for a yacht and the last thing that a skipper wants is to add to the complications by being damaged in a side-issue. The weather, in fact, is not so very bad (indeed I argue that this is a case of giving a dog a bad name), but it is unpredictable and can change with remarkable swiftness. To sail under those circumstances in waters that are not fully charted might be considered imprudent by a yachtsman with limited time. Thus my original aim was simply to chart and index the bolt holes that would be useful to a yachtsman and which were not covered by the Admiralty Pilot. Armed with the knowledge that if a sudden onshore gale was to occur without warning and that there was a convenient anchorage close by, more yachts might explore beyond the Stanley water front.

When the Capricornus sailed into Stanley in the southern autumn of 1979 her arrival coincided with a team from the National Maritime Historical Society (NMHS) of America. This team, led by Dr Eric Berryman of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, had arrived with a view to hiring a boat of any description and visiting the site of the wrecked Vicar of Bray whose bulk lies at Goose Green. There was no suitable craft available except the Capricornus. Capricornus had been built by three Norwegian undergraduates in cement to a Colin Archer design. On graduating, the three, Steffen Tunge, Arild Tvedt and Arne Mikal Enoksen, set off for a circumnavigation before returning to their life’s work in Norway. At each port of call they would earn enough money for the next leg by chartering their yacht. They had found this very lucrative in the Caribbean but, like so many before them, had not been prepared for the way of life in the Falklands.

Having met the two parties independently it was quite clear that there was an easy solution. Capricornus could be chartered, the NMHS would have their transport and I could test the usefulness of my sailing instructions.

The arrangement worked well. As a result, the NMHS completed their survey of the Vicar of Bray from the most satisfactory of bases, I joined the NMHS and carried out a subsequent expedition as navigator with them in the North Sea looking for the remains of John Paul Jones’s flag ship, the Bonnehomme Richard, and we have all become good friends with Capricornus and her intrepid crew. I have a copy of the beautiful book the Norwegians wrote on completion of their circumnavigation, and for an account of sheer professionalism, coupled with a sense of immense fun, it is an unbeatable record of ‘how to do it’ and how to get the maximum enjoyment out of doing so. The Vicar of Bray is now owned (for $1) by the NMHS.

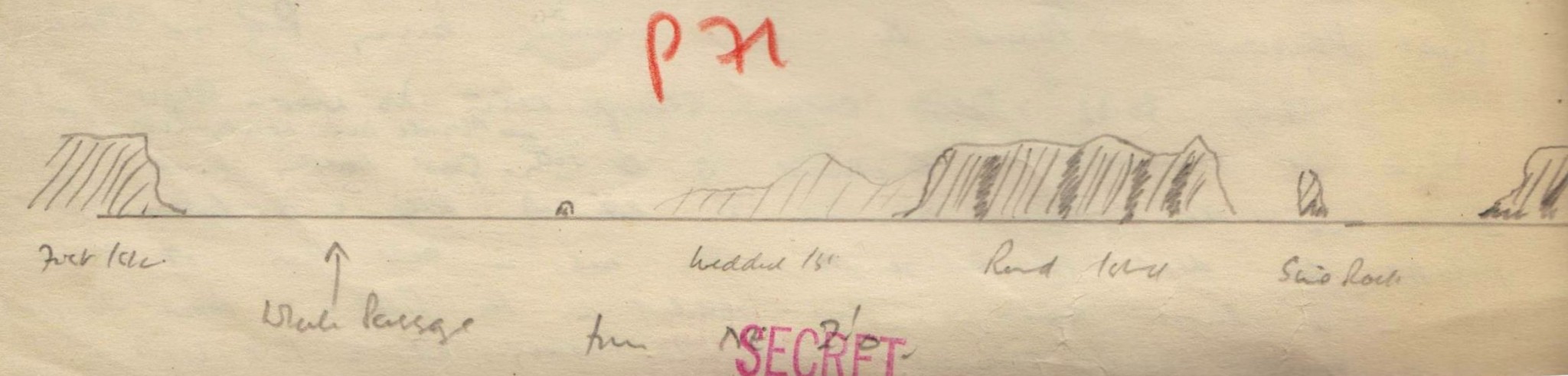

On completion of my year in the Islands I had amassed well over a thousand photographs, two hundred pencil sketches of the coastline, one hundred and fifty pages of notes, and numerous watercolour paintings of the scenery and the seabirds. I had also drawn nearly sixty charts of bolt holes (what the Islanders call ‘catch-ups’) and annotated existing charts of numerous others. In doing so I had sailed just over 6,000 miles. It had never been my intention to make money from this project, indeed I knew it would be impossible even if that had been my aim. I simply felt that such a glorious cruising ground should not go unvisited, and if by compiling a set of sailing instructions I could persuade the occasional yachtsman to share with me this wonderful place I knew that the work would have been worth while. Of course the last thing that any of us wants is to see the Falklands swamped by yachts and even, heaven forbid, marinas.

On return to England I approached a number of publishers with examples of my charts, paintings and coastal profiles. These publishers were all very nice and complimentary but naturally none considered that the work was worth the commercial risk. This did not upset me as I had never been under any illusions about the viability of the project; and so that is where the story ended until 2 April 1982.

On that morning I was recovering from a monthly dinner of the Royal Cruising Club whilst attending a lecture at London University on ‘Oil, Islam and the Middle East’. The Adjutant of the Royal Marines base at Poole contacted me with a message to return immediately. I wasn’t in the mood for jokes and anyway it was the day after April Fool’s Day. He suggested that I listen to the news on the wireless. I did.

At that stage I had no idea that I would be going with the Task Force, but as the head of the Royal Marines Landing Craft branch and knowing that where 15,000 miles of coastline were concerned it would be unrealistic to ignore the potential of waterborne transport, I hoped I would be chosen to advise on these aspects of the campaign. Consequently when I reported, as instructed, to Brigadier (now Major-General) Julian Thompson later that day in his office at the Headquarters of Commando Forces Royal Marines I made the point that I was not to be separated from my precious charts and notes that he had asked to borrow, and that if they went to the Islands I would have to accompany them. It took the Brigadier less than a second to make up his mind about this interloper to his already formed and experienced team of staff officers. Thus began the vindication of all my private work. The subsequent events have no place in this book but throughout the sailing instructions I have included extracts from diaries and logs stretching back to the earlier settlers wherever the place being described has had some part in the history of the Falkland Islands. The recent campaign, therefore, is no exception.

There have been numerous logs kept over the centuries by mariners visiting the Islands which would fill volumes on their own, and so I have chosen logs from only two earlier navigators. The first was Admiral The Hon. George Grey who was instructed to circumnavigate the Islands in his ship HMS Cleopatra in 1836, and the second was Lieutenant Robert Lowcay who commanded His Majesty’s Ketch Sparrow and who described himself ‘Officer in Charge of the Falklands’. Lowcay sailed amongst the Islands the year after Admiral Grey.

Admiral Grey, in particular, used Lieutenant Edgar’s charts (dated 1798) and found them to be ‘less than satisfactory’ in a number of places. At one stage he was forced to write that if a surveyor does not know the answer he should not guess, for this he rightly considered to be a most dangerous practice. I view the sailing instructions as an hors d’oeuvre, a whetter of appetites. Had I had the time and opportunity to visit every single bolt hole and anchorage for inclusion in these sailing instructions I think I might fairly be accused of leaving nothing for future yachtsmen to explore. Thankfully there are still about nine thousand miles of coastline left! These instructions are not designed to replace the Admiralty Pilot (South America Pilot, Volume II) or charts which must remain the authoritative publications on the Falkland Islands, they are merely designed to supplement those documents with a view to helping yachtsmen. To that end I have inserted a number of relevant, and sometimes not so relevant, details and instructions in the hope that the navigator may find the whole more interesting than the average ‘pilot’.

As I have explained, this is not a war book nor is it a history book, but I believe it is interesting to read Admiral Grey’s observations made in the middle of the last century and so I will end this preface by quoting both him and Lieutenant Lowcay to show that in the last hundred and fifty years not much has really changed.

Admiral Grey wrote:

I will now bid good-bye to the Falklands with a few casual remarks and they shall be very few as I am quite tired of the subject…

The first thing to be considered is, whether this colonization of these Islands is advisable or not, if so, whether they are capable of being turned to account and in what manner it would be best to undertake it.

Looking at the map one is immediately struck by their position as presenting a most desirable point for a Naval Station with reference to the great and increasing trade of England with the New Republic of the Pacific. Situated as they are so near Cape Horn, they naturally present themselves as a place of refuge for vessels in those stormy latitudes and considering the numerous safe harbours, ease of access, it would appear as if nature had intended them as such.

The opinion I have found after all the enquiries I have made and from my own observations is this – that the whole matter rests upon whether the Government thinks it an advantage to establish a point of Naval strength or not in this part of the world. Of the capability afforded of forming a thriving colony I have not the least doubt but, as I said before, I consider the question to depend upon whether politically speaking it is not worth while. The expense at the commencement would be trifling if it did not, as I think it would, defray its own expenses from the first; as a matter of colonization alone, one would not recommend barren hills in the fifty-fourth degree southern latitude when there are so many large tracts of uninhabited territories in Canada and New South Wales which hold so many more inducements to the Emigrants.

Lt. Lowcay wrote:

The weather was remarkable fine during our tour as will be seen by the accompanying table of the height of the Barometer and Thermometer [these are in the Government Archives, Stanley] and state of wind and weather, never having had occasion to reef or take in sail on account of the freshness of the wind.

The soil on all the Islands appears to be much the same, and the same wild birds; rabbits are common to all in great numbers. East Falkland possesses advantages of the other Island, in consequence of the wild cattle, from 15 to 20,000 head, wild horses from 5 to 10,000 head but these might be easily transported to the West Falkland from Fannings Harbour to White Rock Harbour a distance of about 7 miles, but would require protection for a few years.

Settlers at Port Egmont and Fannings Harbour (which in my opinion are the next best places to Port Louis) would at first labour under great privations and would have to bring with them at least 12 months stock of bread and flour and wood for building houses; stones are abundant and peat for fuel may be obtained at all islands.

Vegetables such as potatoes, onions, turnips, will I have no doubt grow on any of the Islands as they succeed well at Port Louis but must be protected by high walls as the wind blows occasionally strong during the summer months. Corn on this account as well as from the shortness of the warm weather, I think would never succeed, therefore settlers would have to depend on a foreign country for supplies of corn. Wild hogs are abundant, particularly at Eagle Island (or Speedwell) which from the dryness of its soil compared with the others would make a good sheep farm.

For the protection of the Wild Cattle, Fisheries, Seal Rookeries, etc., on these Islands it would require five vessels of the ‘Sparrow’s’ size and complement; one to cruise during the season between Grantham Sound and Fannings Harbour which places are the resort of American vessels when they require fresh beef, the others for the protection of the Seal Rookeries and Fisheries at the Western Islands with an old 20 gun ship or Bomb stationed as a guard ship at Port Louis as a depot for provisions and stores to supply the cruisers, with a complement of 40 men to be employed in gardening, building, etc. With this force the Islands would be effectually protected from trespassers and the seals in the Rookeries would again become abundant.

In the text I have inserted quotes from my own diaries. The more important of these are from the log I kept during 1978 and 1979 while sailing around the Islands. They convey the feeling I had for certain passages and anchorages, as they are contemporary and describe my immediate impressions. The other diary of mine that I quote was written during the campaign to regain the Islands from the Argentinians in 1982 and as such would not normally have a place in a yachtsman’s guide. I include selected passages from these ‘war diaries’ where I believe that their content is relevant to the beach or anchorage under discussion. They will bring alive certain places for the historically-minded yachtsman. There is only one way to learn how beautiful the Islands are and that is to go and see for yourself.

Ewen Southby-Tailyour

Black Velvet II

Plymouth, June 1983